Wordsworth’s The River

Duddon – A series of Sonnets, first published in 1820, form the opening

work in the ‘third and last volume of the Author’s Miscellaneous Poems’. The book contains thirty other poems, varied

in style and subject matter, including a long narrative romance, Vaudracour and Julia and a reprint of an

extended prose work, A Topographical Description of the Country of the Lakes, in

the North of England. Stewart Wilcox

observes, “none of Wordsworth’s later poems has been so neglected as his sonnet

cycle The River Duddon”.

Though written in 1954, Wilcox’

comments remain pertinent. Kim, writing

in 2006, almost paraphrases the earlier critic,”The River Duddon has been neglected by modern readers. Only

“After-thought” is regularly anthologised:

the other thirty-two sonnets have generated a surprisingly small amount of

commentary”.

This latter point is a key to the critical history of the sonnet series.

Scholars have either treated the work partially, concentrating on the more

sublime sonnets which conclude the series, or they have considered specific

poems within a broader discussion to reinforce a particular viewpoint, rather

than critically evaluating the series in its entirety

For example, Kim, whilst recognising

the issue of ‘part treatment’, nevertheless concentrates his commentary on a

close reading of the final three sonnets to develop his central thesis that

aesthetic considerations of Wordsworth’s ‘middle period’ cannot be de-coupled from

political ones. Kim analyses the final two sonnets from what is an essentially

ideological standpoint. Lines from the concluding sonnet which contrast “sovereign Thames […] / With Commerce

freighted or triumphant War” with “the

lowly mast” found in the Duddon’s “native

stream” are regarded as a reflection of Wordsworth’s increasing nationalism

evidenced in his tract on The Convention

of Cintra (1809).

Whereas Kim focusses his attention on

those sonnets within the series which best support his ideological stance,

Uddin Khan’s essay on the contemporary critical reception of the volume as a

whole asserts how the sonnets generally reflect the volume’s overall

classicising tendencies: ‘the elevated language in which the Duddon is

described – “stately,” “majestic,” “lordly,” “imperial,” and “lofty,” [is]

commensurate with the elegance of diction and the gracefulness of tone throughout

the entire volume.’

More general interest in the sonnet

sequence by leading Wordsworth scholars has been minimal, occasionally

surprisingly so. Jonathan Bate, in a pioneering work of British eco-criticism, Romantic Ecology, Wordsworth and the Environmental

Tradition (1991), utilizes the prose Guide

to the Lakes published in the ‘Duddon volume’ as a central plank of his

re-reading of Wordsworth from a ‘green’ perspective, asserting “the poet is as

much geographer as historian”.

In the book’s final chapter Bate explores “the magic of places” asserting “for

Wordsworth, pastoral was not a myth, but a psychological necessity”.

Given the close parallels between the sonnet series and the portrayal in The Guide to the Lakes as a semi-idyllic

“Republic of Shepherds and Agriculturalists”, then the omission of any mention

of the sonnet sequence in Romantic

Ecology seems surprising.

Similarly, Stephen Gill – author of

the keynote literary biography of Wordsworth – in his essay ‘Wordsworth and The River Duddon’ concentrates on the

dedicatory poem to Wordsworth’s brother, ‘To the Rev. Dr. W –‘, then comments at

some length on remainder of the volume as a ’poetical miscellany’. Consideration

of the sonnet series, however, is glossed over. Like Bate, an in-depth analysis

of the prose Topographical Description is

preferred as the primary vehicle to explore localism in the later Wordsworth.

In the case of Gill, the reason for his apparent neglect of the sonnets may be

gleaned from his earlier biography, where he observes “The whole sequence is

competent, but it concludes magnificently”.

Again, the ‘sublime’ final sonnet is celebrated, but the quality of the series

as a whole is dismissed as merely ‘competent’.

In order to find a piece of substantial

scholarship which considers the Duddon Sonnets

as a whole, one has to rely on Wilcox’ essay from the 1950’s. He makes a good case for seeing the series as

a reflection of Platonic symbolism, concluding:

This emphasis on time is centrally structurally and

philosophically. The stream and Stream, which partitively correspond to nature

and Nature, likewise correspond to man and Man. The Platonic copies in time

suggest the eternal Forms out of it.

Though Wilcox asserts a thematic and philosophical coherence

within the sonnet series, he achieves this by supressing consideration of the

marked stylistic variations within the work. Uddim Khan summarises these

‘traditionalisms’ as “personifications, inversions, picturesque and classical

elements”.

Often in the Duddon sonnets Wordsworth strays far from “the real language of

men” which he advocated in the preface to Lyrical Ballads. Traditionalism here goes

beyond questions of poetic diction; in certain poems Wordsworth adopts an

overtly Augustan aesthetic, the reader familiar with Wordsworth of Tintern Abbey or The Prelude can be ‘wrong-footed’ by such interpolations. What is

the poet’s intention – pastiche, Parody or apostasy?

In the decades following Wilcox’ paper,

literary theory took a distinctly ‘ideological’ turn. Bate, in his introduction

to Romantic Ecology characterises this

as follows:

The 1980s witnessed something of a return to history, a move

away from ahistorical formalisms, among the practitioners of literary

criticism. In the area of English Romantic poetry […] the capstone of the

decade’s criticism was […] by Alan Lui called Wordsworth, The Sense of History.

The conception of ‘ideology’ and ‘history’ underlying these books are in the

broad sense Marxist.[12]

Since the stylistic variations within the Duddon Sonnets -the

mix of Wordsworthian romantic diction with ‘traditionalism’ - render them

difficult to position ideologically, unsurprisingly they have been neglected by

Marxist critics. However, the period since the 1980s also saw the emergence of

post-modernism. Here the ‘neglect’ of the Duddon sonnets is less explicable.

Given the series’ conscious historicism, its lapses into pastiche, and even

parody of the Augustan aesthetic, for scholars interested in a dialogical

rather than dialectic approach then the ‘intertextuality’ and examples of

heteroglossia found within the text may have been expected to have attracted critical

attention. However the work has not been considered in this light. The

intention of this essay is to address this gap.

Scholarship of the past half century has

concentrated on the final ‘After-thought’ sonnet and overlooked the rest of the

work. This is not how the Duddon Sonnets

were considered on publication. Wordsworth himself regarded the series as being

capable of being interpreted as a single work. He writes, “The reader […] interested

in the foregoing Sonnets which together may be considered as a Poem”.

This sentiment was re-iterated by Mary Wordsworth, in a letter from December

1818 she asserting that the Duddon

Sonnets “all together compose one piece.”

Furthermore, the series was critically received in this light. In 1821 the Tory

monthly, British Critic, reversing

its previous antipathy towards Wordsworth, praised the series as follows:

The gem of the volume is a set of sonnets on the River

Duddon, in which the poet, following the stream from its mountain source down

to its mixing with the sea, seizes on all the incidents by the way that strike

his attention. This is a beautiful idea: each incident has the completeness and

unity essential to a sonnet while the stream is the connecting link.

The remainder of this essay will examine the principles upon

which the ‘set of sonnets’ were arranged creating a ‘completeness and unity’

which enabled them to be regarded as ‘altogether one piece’. Furthermore, it will argue that the particular

approach that Wordsworth took to arranging the sonnets signalled a development in

his aesthetic outlook which proved instrumental in changing critical attitudes to

his work in general. There is some truth in De Quincy’s later statement, “Up to

1820 the name of Wordsworth was trampled underfoot; from 1820 to 1830 it was

militant; from 1830 to 1835 it has been triumphant.”

Towards the end of his life Wordsworth acknowledged the role the Duddon sonnets

had played in popularising his work. Speaking to Dr Cairns in 1849 he noted,

“My sonnets to the River Duddon have been wonderfully popular…”

In order to re-discover the Duddon sonnets as a single work I have

undertaken a close, annotated reading of the series seeking to give equal

consideration to each of the sonnets, rather than, as recent scholars have

done, concentrating only on those which are deemed ‘successful’ or most

ideologically suited to sustaining a particular critical stance.

This will then be considered in relation to Wordsworth’s reflections on poetic

theory contained within the Preface of 1815. The preface represents a

considerable development in the scope or Wordsworth’s thinking about poetry, He

seeks to reconcile his radical theories regarding poetic diction found in the

more famous Preface to Lyrical Ballads (1800) with notions of taste, decorum

and Form inherited from Augustan verse and the Classical traditions.

The ‘re-reading’ has also been

influenced by Don Peterson’s recent ‘new commentary’ on Shakespeare’s sonnets.

In the introduction Paterson distinguishes between two kinds of reading: secondary reading – associated with

literary criticism which seeks to unpack “a poem’s multiple senses [by] the

careful analysis of its deep structure”, and primary reading, which “engages with the poem directly as a piece

of trustworthy human discourse”. Paterson’s approach was refreshingly simple -

he read and annotated two sonnets a day “fitting them round work routine and

domestic obligations, into leisure and dead time”. I simply emulated his approach annotating a sonnet

a day for a month; these notes were subsequently copied into the following

blog: http://imaginedelsewhere.blogspot.co.uk/

The process of ‘primary reading’ did

provide an insight into the structure and shape of the whole series, but

initially the results appeared ambiguous. One was aware of a simple,

over-arching structure: the river rises in the mountains, “a Child of the

clouds”, and “sinks' into the 'Deep” in the final sonnet. Wilcox has summarised

this 'arc' succinctly:

“Keeping in mind then that the Duddon in

its growth and moods not only reveals the activities of various stages of life,

but also is symbolic of man's spirit as it emerges from the unknown, runs its

earthly course, and merges again with the eternal , […] Wordsworth uses the

river to give them coherent development.”

Wilcox' anthropomorphic reading of the series is not entirely

invalid, but it only applies in parts. Just as many of the sonnets undermine his

vision of 'coherent development' as assert it. The series is characterised by

variety, ambiguity and interpolation as much as displaying a centralising

theme.

Ambiguity is signalled from the

outset. Sonnet I opens in a classicising mode, alluding to a 'Horatian lyre',

the spring of Bandusia, and evokes the Duddon as a Muse. Wordsworth, even in

his most Epic moments, in the opening lines of The Excursion' or The Prelude,

does ‘summon’ the Muse so directly. Clearly the ' epic' opening deliberately

invites the reader to accept this 'native stream' as a subject suitable for

treatment in 'the grand manner'. Even here there is ambiguity. The Spring of

Bandusia refers to Horace's hymn to Spring - Ode

III, 13. Horatian Odes belong to the lyric, rather than the epic

tradition. Wordsworth asks for the

Duddon series to be seen in the same light as Horace's short, lyrical odes

which were collected together into 'themed' books. However, the Duddon Sonnets is multi- faceted; an

overriding narrative structure is provided by the motif of the river, but a

recurrent subsidiary theme is woven throughout which addresses questions of poetic

tradition, genre, and diction.

Throughout the series narrative flow

is diverted by interpolations of various kinds: Sonnet VII is a parody of a

Petrarchan love poem; Sonnet XXIV adopts the tone of the Augustan pastoral;

Sonnet XXIV seems typically Wordsworthian

- like a snippet of The Prelude,

Book II; Sonnet XXIX takes a didactic, moralising turn. At the stage of primary reading such apparent

thematic diversions can be frustrating appear inexplicable in relation to the

poem's overall narrative structure.

Indeed it can be tempting to regard them as detrimental to the work's

coherence and judge the series as a miscellany masquerading as a sequence. It

may be that such an initial response accounts for the general critical neglect

of the work.

However, this does not take into

consideration that critical comment at the time of publication praised

specifically the series' structure and form.

Moreover Wordsworth insisted that the sonnets should be read as a single

poem. In order to understand contemporary attitudes towards the work we must

re-examine the principles upon which the poems were arranged. The remainder of the essay will attempt to do

this by analysing the poem in the light of the literary theories developed in

the preface to the 1815 edition of Wordsworth’s collected poems.

Critical responses to Wordsworth were prompted as much by the content of the

prose Prefaces as the poems themselves. As

Uddim Khan points out:

“Although mixed and completely

favourable reviews were not very scarce, adverse and abusive reviews were

overwhelming by comparison. Ever since the 1800 Preface to the epoch-making Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth was plunged

into critical controversies surrounding his poetic theory in practice. In the Annual Review of 1808, Lucy Aitkens took

issue with his theory of poetry as submitted to the Public in that Preface.”

In particular, Aitkens “argued for bold sweep of wit, fancy

and imagination, and richly figurative and truly poetical diction”.

Though Gill, in William Wordsworth – A Life is somewhat dismissive, agreeing with

the Monthly Review’s assessment of the 1815 Preface as “neither remarkable for

clearness of idea nor for humility of tone”, nevertheless, it provides us with

the most comprehensive account of Wordsworth’s response to Aitken, critique of

his poetic theory and provides insight into his method of arranging shorter

poems thematically.

Wordsworth begins the Preface by

listing the qualities of the poetic mind: Observation, Sensibility, Reflection,

Imagination and Fancy, and Invention. He then enumerates the main forms of

poetry – Epic, Lyric, Pastoral etc., and illustrates them using both classical

and English examples.

This is neither controversial nor innovative. Where the Preface does become

more interesting is in the following section where Wordsworth begins to articulate

his own approach to classifying or ordering collections of poetry: “It is deducible from the above,

that poems apparently miscellaneous may with propriety be arranged either with

reference to the powers of mind predominant in the production

of them.”

The poet is keen to point out that this requires flexibility, acknowledging that

most poems are multi-modal: “I wish to guard against the possibility of

misleading by this classification, it is proper first to remind the Reader,

that certain poems are placed according to the powers of mind, in the Author’s

conception, predominant in the production of them; predominant, which

implies the exertion of other faculties in less degree.”

Wordsworth’s awareness of differing reading strategies in this regard is

interesting. He makes clear his desire to accommodate the needs of both

‘unreflecting readers’ and the more discerning by balancing engaging variety

with thematic unity.

“Where there is more imagination

than fancy in a poem, it is placed under the head of imagination, and vice

versâ. […] The most striking characteristics of each piece, mutual

illustration, variety, and proportion, have governed me throughout”

The discussion of the differences between fancy and

imagination which follows is crucial to understanding how Wordsworth conceived

the Duddon Sonnets as ‘one poem’. He

explores the modes of fancy and imagination from two standpoints. Firstly, he

presents these two notions as poetic ‘meta-categories’ and differentiates

between their broad subject matter - succinctly summing up the difference in

the phrase” “Fancy is given to quicken and to beguile the temporal part of our

nature, Imagination to incite and to support the eternal.” Thus ‘fancy’ “is as capricious as

the accidents of things, and the effects are surprising, playful, ludicrous,

amusing, tender, or pathetic, as the objects happen to be appositely produced

or fortunately combined.” However, ‘imagination’ “is conscious of an

indestructible dominion;—the Soul may fall away from it, not being able to

sustain its grandeur; but, if once felt and acknowledged, by no act of any

other faculty of the mind can it be relaxed, impaired, or diminished.”

This fundamental

difference in mode is mirrored in the way the two categories function

poetically. For Wordsworth, the difference resides in how metaphor works within

each category. Following an extended

analysis of the two terms in “British Synonyms discriminated, by W. Taylor” and a critique of Coleridge’s ideas from Biographia

Literaria, Wordsworth illustrates the difference by way of example.

Commenting on Cotton’s Ode Upon Winter, metaphor is characterised by “a

rapidity of detail and a profusion of fanciful comparisons, […] and a correspondent hurry of

delightful feeling.” The Fancy tends towards comparisons which are simple,

profuse and ephemeral. Seldom reticent

to assert his position in relation to illustrious antecedents, Wordsworth

considers the function of metaphor within poems of imagination, firstly in

Virgil, then in Shakespeare, before reflecting on his own ‘To The Cuckoo’. In poems of Imagination imagery may be more sparse,

but more striking and enriched with multiple associations which ‘grow‘on the

reader. To paraphrase this distinction in current terminology, Wordsworth

suggests imaginative metaphors operate primarily through connotation whereas as

‘fanciful’ ones are more denotative.

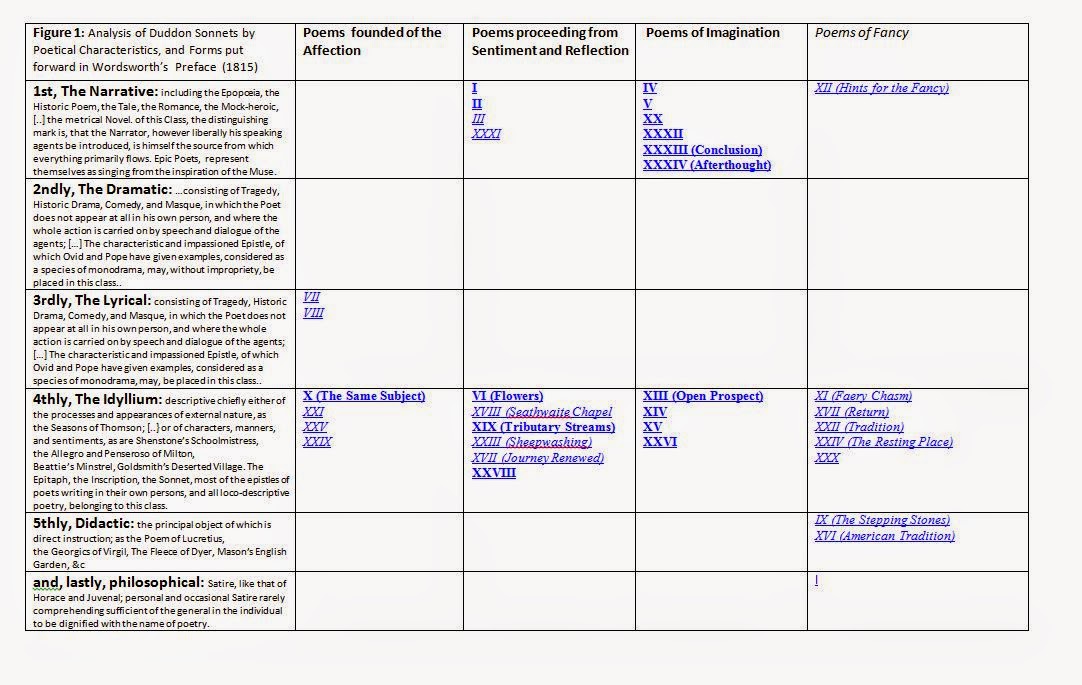

How these

theories assist us to appreciating the structure of the Duddon Series is

illustrated in Appendix 1, figure 1. Here the individual sonnets have been

analysed in relation to the poetic forms and classes set out in the Preface.

Each poem has then been assigned as belonging to either the category of Imagination

(bold) or Fancy (italic). To assist in linking the analysis back to the

original compositional order, the sonnets have been hyperlinked to the text and

notes in the ‘primary reading’ blog. Admittedly such a process of ‘reverse

engineering’ from theory to text is not without its limitations; the process of

critical analysis will always be an approximation of the how Wordsworth’s theory

and practice inter-related. Nevertheless the process is instructive. What

emerges is a structure in which the pastoral mode (Idyllium) predominates, but

where the Epic, utilising the recurrent motif of the river as “guide and

friend”, forms an overarching narrative arc - concentrated particularly at the

series’ opening and closing sections. For this reason I have termed the series,

‘An Epic of Fancy’.

In relation

to Imagination and Fancy, analysis shows that there is almost an exact balance

between the two modes. The resultant poem embodies the kind of poetry that Lucy

Aitken called for in her critique of the Preface to Lyrical Ballads: “a bold sweep of wit, fancy and imagination,

and richly figurative and truly poetical diction.”

One senses Wordsworth, without abandoning his original tenets – he continued to

revise and develop the unpublished Prelude

throughout this period – nevertheless was responding consciously to the

more negative aspects of contemporary criticism of his work.

What such structural analysis cannot

reveal is the versatility of Wordsworth’s technique in achieving this,

switching between Augustan ornament and more austere contemporary diction with wit

and studied virtuosity. For example, Sonnet VI ‘Flowers’ adopts a deliberately

ornate, Augustan voice:

…And caught the

fragrance which the sundry flowers,

Fed by the stream with soft perpetual showers,

Plenteously yielded to the vagrant breeze.

(Ll.

7 – 9)

The language is reminiscent of the idyllic pastoralism of James

Thompson’s The Seasons (1730.)

However, the sonnet which follows is an overt parody of such classicising

tendencies:

"Change me, some

God, into that breathing rose!"

The

love-sick Stripling fancifully sighs,

The

envied flower beholding, as it lies

On

Laura's breast, in exquisite repose;

(Sonnet

VII, LI. 1 – 4)

For

all the Duddon Sonnets’ preoccupations with ‘traditionalism’, it would not be

correct to represent the series as wholly retrospective. The poet of Tintern Abbey and Lyrical Ballads re-appears occasionally:

….for fondly I pursued,

Even when a child, the

Streams--unheard, unseen;

Through tangled woods, impending

rocks between;

Or, free as air, with flying inquest

viewed

The sullen reservoirs whence their

bold brood--

Pure as the morning, fretful,

boisterous, keen,

Green as the salt-sea billows, white

and green--

Poured down the hills, a choral

multitude!

(Sonnet

XXVI, Ll 1 – 8)

Furthermore,

Wordsworth reveals his awareness of contemporary developments in natural

science. In the final lines of Sonnet

XV, the poet speculates on the formation of unusual rock formations at

Wellbarrow ravine:

Was it by mortals

sculptured?--weary slaves

Of slow endeavour! or abruptly cast

Into rude shape by fire, with roaring blast

Tempestuously

let loose from central caves?

Or

fashioned by the turbulence of waves,

Then,

when o'er highest hills the Deluge passed?

(Ll. 9 –

14)

This

reflects Enlightenment ideas concerning the origin of the earth known as

catastrophism; it alludes to both the ‘Volcanism’ of Hutton and the ‘Neptunism’

of Buckland and Lyell; significantly, the prevailing Christian orthodoxy of

‘creationism’ is not mentioned.

Other contemporary concerns are

reflected in the sonnets ‘Open Prospect’ and ‘Sheep Washing.’ Here the ‘living

landscape’ of the Duddon Valley is explored in terms which mirror the concerns of

the Guide to the Lakes. Both the Guide and the sonnets offer a critique

of the Picturesque. Wordsworth was acquainted with both William Gilpin and

Uvedale Price, leading writers on the Picturesque. To some extent he was a

proponent of the Picturesque himself. Sonnet III

opens posing the question to the river Duddon “how shall I paint thee?” The

answer - in the ‘viewing instructions’ as to how to observe the Duddon from

Walnar Scar found in the note to Sonnet XVII; the lengthy musings on correct

tree planting included in The Guide; the

idealised depiction of “ruddy children” by a “Cottage rude and grey” in Sonnet V –

suggest the aesthetics of the Picturesque. However Wordsworth was ambivalent

towards the Picturesque; he was interested in dwelling within landscape as much

its appearance – what the social anthropologist, Tim Ingold calls the

‘taskscape’.

This interest permeates the entire Duddon Volume: in the extended memoir of the

rural pastor, Rev. Robert Walker; the sections of The Guide which concern “The Republic of Shepherds and

Agriculturalists”; and in the sonnets – number VIII’s

speculation about the “first tribes” of the valley, the depiction in Sonnet

XIII, of the fields “clustered with barn and byre and spouting mill” and in XXIII -

‘Sheep Washing’. Moreover, the

magnificent final sonnet does not conclude with a consideration of Nature

itself, but with a reflection on how man dwells within it:

While we, the brave,

the mighty, and the wise,

We Men, who in our morn of youth defied

The

elements, must vanish;--be it so!

Enough, if something from our hands have

power

To

live, and act, and serve the future hour…

(Sonnet XXXIV, Ll. 7 –

12)

This Essay has sought to treat

the Duddon Sonnets in the manner which the poet preferred– “as one poem”. The work which emerges is

an example of what Wordsworth termed in the Preface, “composite” form The Duddon Sonnets moves between the epic and idyllic mode; it attempts

to balance poems of Imagination and Fancy within a single compositional

framework. This is achieved with skill, variety and invention, displaying an

impressive grasp of the genre, technique and diction from differing epochs.

Very few of the sonnets, for all their historicism, are simply derivative or

lapse into pastiche. The work, In terms of subject matter, engages with major

concerns of the day related to literary theory, aesthetics, the Picturesque and

natural science. Given these qualities

it is unsurprising it was greeted on its publication with critical acclaim.

However, these qualities of

variety and stylistic ambiguity may have contributed to the work’s subsequent

critical neglect. The eclecticism of the Duddon Sonnets is not amenable to

analysis which seeks to place it within a particular ideology, movement or

style. Critical developments in recent decades, embracing intertextuality,

poly-vocalism and heteroglossia, may provide more appropriate analytical tools

to study ‘awkward’ works which cut across canonical conventions.

Postmodernism’s broadly dialogical approach enables us to arrive at a more nuanced

view of Duddon Sonnets, re-positioning

it within Wordsworth’s oeuvre and enriching our understanding of the rapidly

evolving literary culture of the late Regency period.